In one of the surest signs that spring has sprung, professional baseball is back. Even better, rising temperatures and rising vaccine numbers mean that fans can again enjoy it in person by visiting one of the very many ballparks in the region – from Nationals Stadium in D.C. or Camden Yards in Baltimore, to the minor league homes of the Aberdeen IronBirds, Delmarva Shorebirds, Frederick Keys, Hagerstown Suns, or Bowie Baysox.

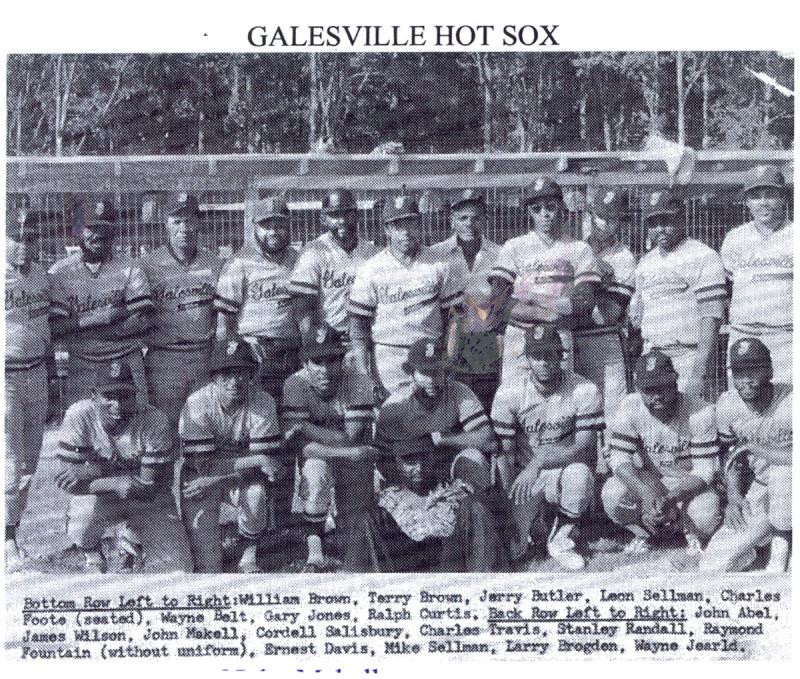

Image courtesy of Galesville Community Center Organization, Inc. Archival Collection

Annapolis even has its own hidden gem, Terwilliger Brothers Field at Max Bishop Stadium, where you can watch the U.S. Naval Academy’s baseball team play one of the 11 games remaining on its schedule for the very affordable price of zero dollars. But if you want to gain a deeper appreciation for and fuller knowledge of Maryland’s rich baseball history, the Negro Leagues should be a part of it. Just ask Maryland’s favorite ballplayer.

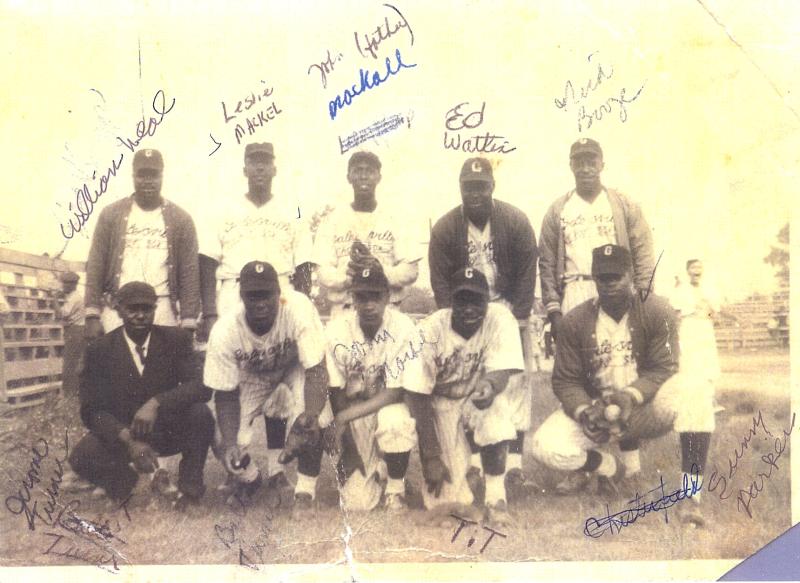

Image courtesy of Galesville Community Center Organization, Inc. Archival Collection

“The Negro League players were true trailblazers,” says Cal Ripken, Jr. “I love the fact that so many of them played in and around Maryland and that they are now getting much of the recognition that is so well deserved. When we played the Royals in Kansas City we all loved spending some time with Buck O’Neil, a terrific guy and a great storyteller, and it’s great to see the memory of these players continue and live on as they should.”

Though it came as a surprise to Cal (and me!), Negro League players not only played throughout Maryland, but also right in Anne Arundel County, at a place called Hot Sox Field. Located in Galesville, in Southern Anne Arundel County, Hot Sox Field was home to, you guessed it, the Galesville Hot Sox – a semiprofessional “sandlot” baseball team founded in 1915. And as I learned from Lyndra Marshall, who serves as the Galesville Community Center Organization (GCCO) historian and researched the team in preparation for a 2015 Smithsonian traveling exhibition, the field is well worth a visit today, serving as a symbol of both a segregationist past and a proud African American culture.

Image courtesy of Galesville Community Center Organization, Inc. Archival Collection

First off, what was sandlot baseball?

Sandlot baseball, named for the dusty fields on which it was often played, was a foundation of African American community life across the United States. It provided recreation for local boys and men, entertainment for their fans and families, and a sense of shared purpose for all. That was what I experienced as a child when my father, who played for the Drury Giants in Lothian, Maryland, would yell “Play Ball.”

Image courtesy of Galesville Community Center Organization, Inc. Archival Collection

When did it start in Galesville?

The Galesville Hot Sox was formulated in 1915 as a traveling sandlot baseball team made up of members of the thirty to forty African American families who lived in Galesville. Many of them were descendants of slaves and sharecroppers, and many of these first players would become role models to younger players in the future.

Many Hot Sox attended or joined the team after attending the Rosenwald School, a one-room elementary school for African American children that was built in 1929, expanded to two rooms in 1931 as part of the Julius Rosenwald Program, and closed in 1956 when students began being bussed out of the village.

At the end of each season the players, most of whom worked as shuckers and oystermen at Woodfield’s Oystery and Fish Company in the early years, earned $50 to $100 raised from monthly dues, attendance fees, and fish fries – and some of them even received bonuses for outstanding play during the season!

Image courtesy of Galesville Community Center Organization, Inc. Archival Collection

Where did they play?

The team played on an open field on West Benning Road until 1926, when the Rosenwald School was built on the site – very appropriately, the same site where the Galesville Community Center now sits. The team then relocated to its present location at Hot Sox Field at Wilson Park. At that time the property was owned by Henry Wilson, a former slave who bought his freedom in the 19th century, and although he’d originally envisioned using the land for senior housing he ended up renting the grassy 26-acre lot to the Hot Sox team for $50 a season, which ran from April through September.

The ball field had two cinderblock dugouts, a rickety wooden stand, and a backstop that became very well-worn over the decades.

Anne Arundel County acquired the field in 2013, after a three-year effort, and former House Speaker Michael E. Busch threw out a first pitch that May in a ceremony attended by Galesville residents, Anne Arundel parks officials, and many former Hot Sox.

Since then the county and the community have worked together to make renovations to the field, for example replacing the wooden stands with metal ones, and make it more accessible for the public and youth teams while still keeping the design compatible with the Negro League era of the 1920s to 19502.

Image courtesy of Galesville Community Center Organization, Inc. Archival Collection

Who’d the Hot Sox play?

Major league baseball was closed to Black players, so independent African American teams such as the Hot Sox booked themselves as if they were a traveling group of entertainers, competing against each other so that they could perfect their games and proclaim colored (as they were referred to back in the day) champions, who became local heroes, each year.

The Hot Sox played in the Bayside Independent League and held their games on Wednesdays; Saturdays, when volunteers and former players could join in; Sunday afternoons after church, which was known as ‘double hitter day;’ and sometimes on holidays. Known as a “head team” because they played smart baseball, for example regularly employing pickoffs, the Sox were among the best around and usually outplayed local teams from Dorsey, Parole, Owens Station, Bare Road, Edgewater, Benedict, Calvert County, Tracey, and Ridge, as well as the Davidsonville Clowns and the Drury Giants.

There was also a Negro Leagues matchup game once a year, against the Baltimore Black Sox or the Newark Eagles, and although the Hot Sox weren’t always a match this gave the players a chance to show out. In fact, sandlot teams served as informal farm clubs for the Negro League teams that began playing in the 1920s.

Image courtesy of Galesville Community Center Organization, Inc. Archival Collection

Did any Hot Sox ever make it on to a Negro League team?

Yes, as a semi-farm team the Hot Sox sent up players to the Negro Leagues from time to time. Several Hox Sox players even earned tryouts with the majors eventually.

Some of the most notable included Tommy Sesker, who joined the team in 1951, threw 90 miles per hour, and got a look with the Baltimore Orioles in 1955; Chester Turner, a first baseman and center fielder who tried out for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1958; and my relative John Makell, Jr. (aka Schoolboy), a second baseman and shortstop who joined in 1947 and was signed by the Baltimore Orioles in 1955 but unfortunately never played for the team after hurting his arm in spring training.

Image courtesy of Galesville Community Center Organization, Inc. Archival Collection

What were game days like?

Just like the players, many residents of Galesville worked all week at Woodfield Fish & Oyster Company, where they shucked oysters and cut and cleaned fish, crabs, and shrimp. It was labor-intensive work, so weekend baseball games were a big celebration with fellowship, food, and fun.

Hundreds and as many as 1,200 spectators paid fifty cents at the gate to watch and cheer the team on at any given game, whether against other sandlot teams or against major league teams such as the Homestead Grays, Indianapolis Clowns, Newark Eagles, and Baltimore Elite Giants.

Games were a time to mingle and enjoy lots of great food for as little as 10 cents – there was always fried fish and fried chicken, crab cakes, hot dogs, green beans cooked with ham bone and a little bit of bacon fat, potato salad, slices tomatoes, rolls, and pies. The menu never changed, and it always sold out.

The team, and cheering it on, really became the foundation of a proud community.

Image courtesy of Galesville Community Center Organization, Inc. Archival Collection

What did the Smithsonian Exhibition in 2015 involve?

The Maryland Humanities Council's Museum on Main Street program, in coordination with the Smithsonian Institution, selected Galesville to host a traveling exhibition, titled “Hometown Teams: How Sports Shaped America,” for six weeks in the summer of 2015. The overarching goals were to increase awareness of the history of Galesville, promote heritage tourism to the town, garner local interest and support, and help to preserve the community and enhance the appreciation and stewardship of the town's cultural, historic, and natural resources.

We developed a companion component at the Galesville Community Center to showcase how much sports has influenced African American culture and brings people together, particularly in local communities, and the Hot Sox were a huge part of it – which was especially special since it was their 100th anniversary year. For me, the exhibit was just another opportunity to tell the untold story of an African American community.

GCCO also organized a community day event to capture stories, pictures, and artifacts (caps, jerseys, socks, rings, bat and gloves) from former Hot Sox players; take their portraits to add to an amazing documentary story quilt, which also includes pictures of equipment and oral histories; and dedicate a walking path that students used to walk from the schoolhouse to the ballfield. The day also included a reunion of players and a reunion ballgame, complete with fried fish, fried chicken, crab cakes, and hot dogs, all priced at ten cents just like the old days.

Although the Hometown Teams exhibit was only on display for six weeks in the summer of 2015, the full Hot Sox Exhibit remains and the public can make arrangements for viewing.

Finally, what’s next for the field?

While we’ve made a number of improvements to the field since the county acquired it, in 2013, we’re excited for major renovations to begin on what will become a $2.5-million state-of-the-art ballpark this summer – hopefully to be completed by the end of 2021 or in early 2022.

This will include constructing The Michael E. Busch Pavilion, named after the man who was instrumental in the renovation of the ballpark and worked tirelessly with GCCO in its planning. It will be a place where the community will come together for recreation and fun, and the public can support the effort by purchasing a $100 paver that will be laser-engraved with whatever inscription they wish, through GCC.

Image courtesy of Galesville Community Center Organization, Inc. Archival Collection

To see Hot Sox Field at Wilson Park in person and imagine the thousands of games that have been played on it, visit it at 862 Galesville Road, Galesville, MD 20765. To see Hot Sox memorabilia and learn more about Galesville, visit the Galesville Community Center at 916 Benning Road, Galesville MD 20765. Finally, check out the Field Guide to Galesville to learn more about Galesville’s rich history and how to experience it in person.