It would have been a blast to go to Carr’s Beach in the 1950s and 1960s. Carr’s Beach was an extremely popular Chesapeake Bay resort and concert venue for the African American community during the racial segregation years of the 1900s. Unfortunately today, Carr’s Beach no longer exists as a venue or beach destination, but its legacy lives on.

Live Music at Carr’s Beach

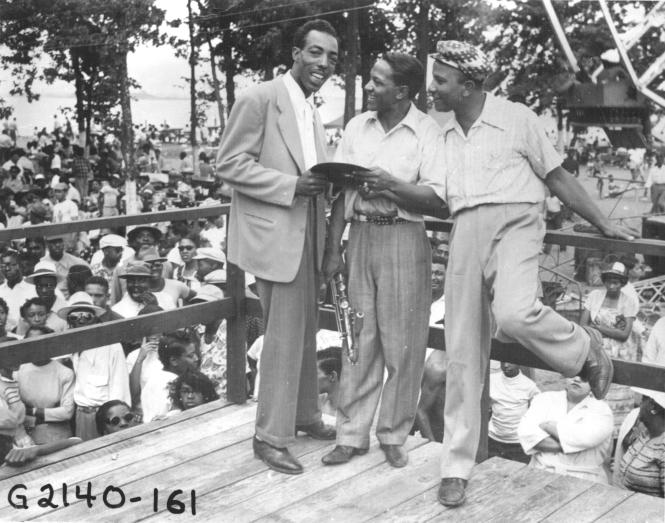

Affectionately called “the Beach,” Carr’s Beach hosted many major African American artists performing for black audiences during the forties, fifties, and sixties. Located on the Annapolis Neck just south of Annapolis, Carr’s Beach was one of several private bayside beaches in use when pervasive segregation denied African Americans access to white-only beaches and facilities. In this intense era of Jim Crow laws and forced racial segregation, black audiences and artists responded out of necessity by creating their own recreational attractions and performance venues. The result for Carr’s Beach was its prominence as a phenomenally popular and successful African American attraction.

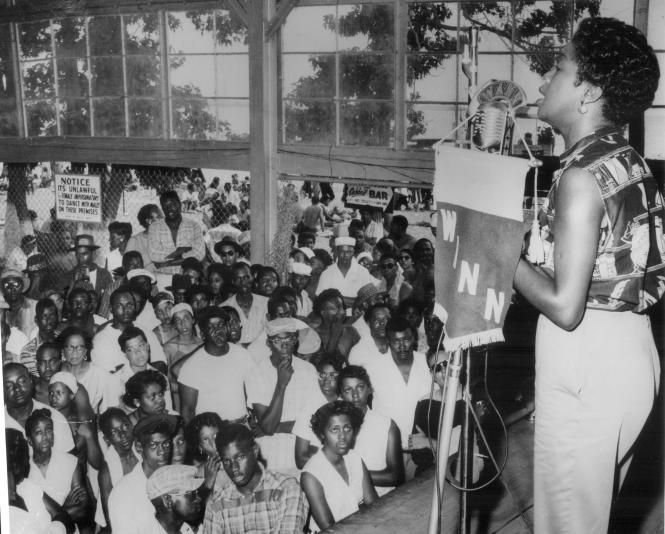

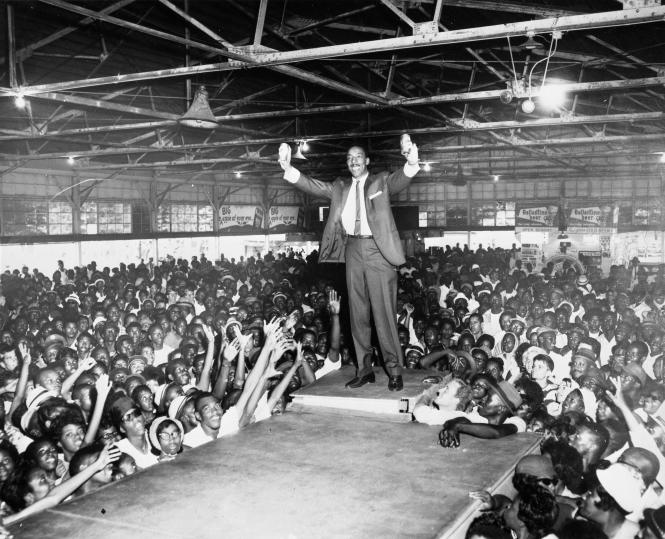

At one Carr’s Beach event on July 21, 1956, an estimated 70,000 people traveled to the Beach to see Chuck Berry perform, but only a lucky 8,000 could be accommodated on the grounds. A 1962 performance there by James Brown drew 11,000 fans. Some of the biggest names in what was then called “race music” played at Carr’s Beach, including these; Cab Calloway, The Temptations, Ike and Tina Turner, The Shirelles, Little Richard, and Billie Holiday, just to name a few.

These and other accomplished African American musicians traveled a route from one performance venue to another that came to be called the Chitlin' Circuit. The term Chitlin’ comes from a soul food dish made from pig intestines called chitterlings, a part of the culinary history of African Americans.

The venues on the Chitlin’ Circuit hosted African American performers and audiences, providing a creative outlet for what turned out to be world-class entertainment. The route took musicians, comedians, and other entertainers throughout the eastern and southern United States to those places and audiences that offered commercial and cultural acceptance for blacks. Carr’s Beach was often the last stop for entertainers who played in Baltimore or Washington, D.C., before heading south.

In addition to Carr’s Beach, other Chesapeake Bay beach communities and ventures on the Annapolis Neck catered exclusively to black guests between 1930 and 1970. Next door to Carr’s Beach was Sparrow’s Beach, on the site of today’s Chesapeake Harbor development, and nearby Elktonia Beach was on the site of today’s Bay Woods. Others included Bembe Beach, Highland Beach, Venice Beach, Oyster Harbor, and Arundel-on-the-Bay.

The Chesapeake beaches were a welcome place for black families to swim, boat, fish, socialize, and enjoy first-class entertainment without harassment. The beaches and musical performances also inspired a sense of group empowerment and the collective strength to resist segregation.

The Origins of Carr’s Beach

In 1902, the formerly enslaved Frederick Carr and his wife Mary Wells Carr purchased 180 acres of waterfront farmland on the Annapolis Neck at the end of what is now Edgewood Road. In addition to farming, the Carr family took in boarders and hosted picnics and outings, and in 1926 they founded Carr’s Beach as a beach retreat for black families. Their daughter, Elizabeth Carr Smith, operated Carr’s Beach, and her younger sister, Florence Carr Sparrow, created the adjoining Sparrow’s Beach in 1931. They operated the two resorts side-by-side as separate businesses.

Over many years, hundreds of thousands of visitors frequented both Carr’s and Sparrow Beaches to swim and picnic on the wide sandy beaches. These beachfront facilities were strong employers and boosted the local economy with the influx of guests attending church picnics, day camps, concerts, and community events. In the late afternoons and well into the night, crowds filled the Carr’s Beach pavilion for rollicking dances and concerts.

When Elizabeth Carr Smith died in 1948, her son Frederick teamed with Baltimore businessman William L. “Li’l Willie” Adams to form the Carr’s Beach Amusement Company to operate the property. Adams invested $150,000 with Elizabeth Carr Smith’s heirs to expand the Beach’s entertainment and recreation facilities. The improvements included building a midway lined with slot machines and amenities and opening a nightclub called Club Bengazi. The changes made Carr’s Beach extremely popular, partly because Anne Arundel County was the first Maryland county to legalize slot machines, and partly because the nation was experiencing an exciting new level of interest in jazz, rhythm & blues, and rock and roll music.

The Energy of Hoppy Adams

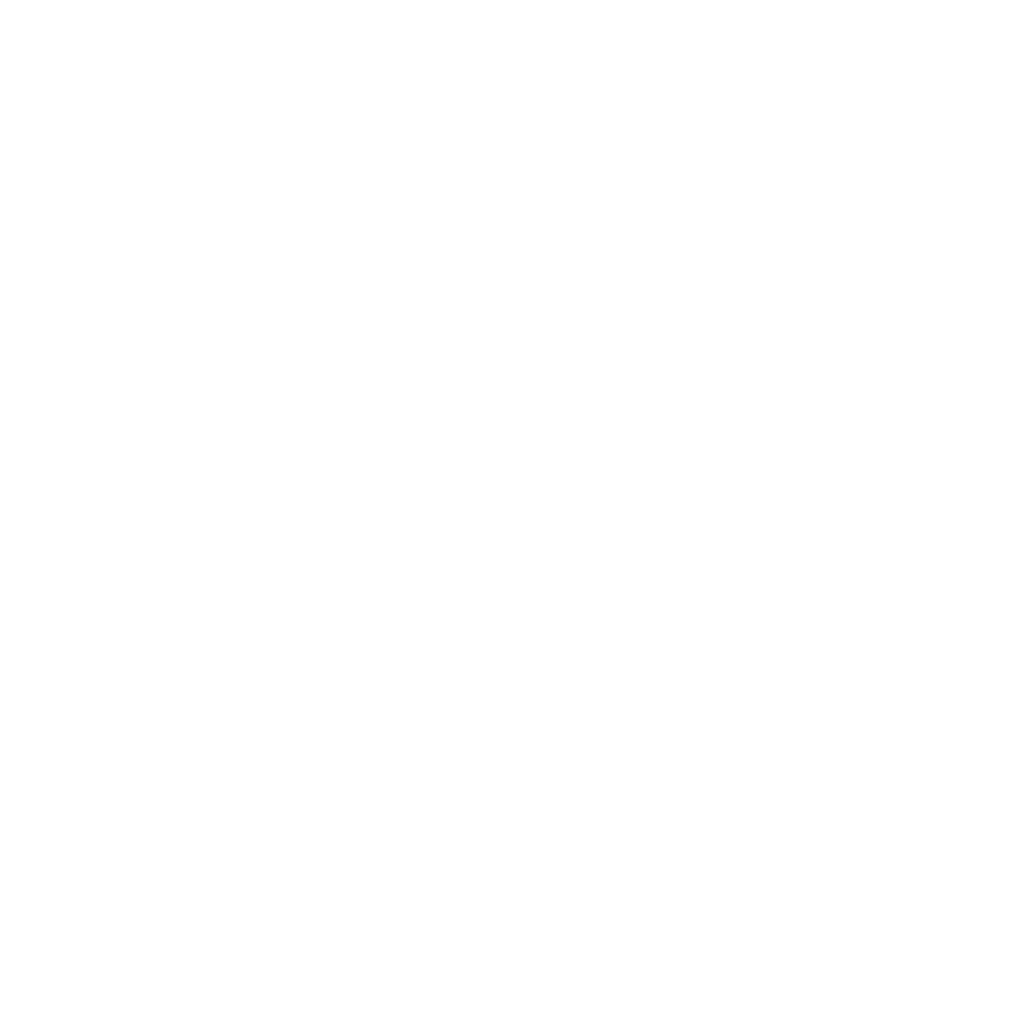

Many huge events at Carr’s Beach were hosted live and via radio broadcast by Charles W. Adams, Jr., better known as Hoppy Adams. Hoppy Adams was a beloved disc jockey and executive with the Annapolis radio station WANN. The WANN radio station at 1190 on the AM dial was created by Jewish entrepreneur Morris Blum, who operated the station for five decades and hired Hoppy Adams in 1952. WANN was novel in those days because it aired gospel, soul, and rhythm and blues music, and its programming catered exclusively to the African American community. Hoppy Adams was WANN’s star personality, and Adams and Blum enjoyed a successful collaboration for more than thirty years.

With Hoppy Adams promoting its events, Carr’s Beach hosted many crowded concerts and dance contests among African Americans from Annapolis, Washington, D.C. Baltimore, and beyond. The Beach employed a team of black Special Deputy Sheriffs to keep the crowded events safe. White visitors who enjoyed good black music also attended the events at Carr’s and Sparrow’s Beaches, at a time when interracial crowds were rare. My own husband, who is white, remembers witnessing a concert attended by blacks and whites together after he climbed a tall fence to sneak into Carr’s Beach for a sold-out summer event in the early 1960s.

There were also a few restaurants that served blacks along the way to and from the beaches. One was the popular Clover Inn "juke joint," open from the 1930s to the 1970s, where beachgoers could find food, drink, music, and dancing. Other establishments along the roads leading to the beaches included Minnie's Inn, Dew Drop Inn, and Winfield's barbecue shack. All these restaurants are long gone now, and only a few concrete vestiges of the Clover Inn remain visible.

When the Jim Crow era ended in the late 1960s through the perseverance of the black civil rights movement, other venues that were once white-only began to open to black performers and attendees. Thus, the popularity of the black-only beaches declined. Carr’s Beach had new owners in the late 1960s, who attempted to appeal to a new audience and bring back the resort’s heyday with performers such as Led Zeppelin and Rare Earth. In 1973, Frank Zappa provided the last performance at Carr’s Beach. The true heyday of Carr’s Beach was in the mid-1900s, well remembered by many Anne Arundel County locals.

A special thank you to Maria A. Day, Director of Special Collections at the Maryland State Archives. Photographs were used and selected with special permission by the Maryland State Archives specifically for this article and may not be reproduced in any way. For more information about the photos in this article from the Blacks in Annapolis special collection, visit them here.

Learn more about African American Heritage in Anne Arundel County at:

African American Heritage & History | Anne Arundel County, MD (aacounty.org)

African_American_Heritage_Guide.pdf (aacounty.org)

To read more about Hoppy Adams and hear a 1966 Carr’s Beach radio commercial, go to C.W. Hoppy Adams Jr. Foundation | All Rights Reserved – Hoppy Adams Foundation

Find out more about Carr’s and Sparrow’s Beach at:

(20+) Remembering Carr's and Sparrow Beaches | Facebook

AGO - Carr's Beach - UpStArt Annapolis (upstart-annapolis.com)