The saying “if this old house could talk” is at the heart of the work of archeologists and historians restoring the Maynard-Burgess House at 163 Duke of Gloucester. Why bother solving the mysteries of an old middle-class home? Because for 143 years the house was continuously owned, occupied, and improved by two families of free African Americans: the Maynard family from 1847 to 1914 and the Burgess family from 1914 to 1990.

The Maynard-Burgess House and records from the time provide insight on how free African Americans lived alongside their white neighbors from the time when most black Americans were enslaved to the post-Civil War period when racism remained ever present. The history of the house has been revealed nail by nail and beam by beam, and the grounds have been thoroughly examined.

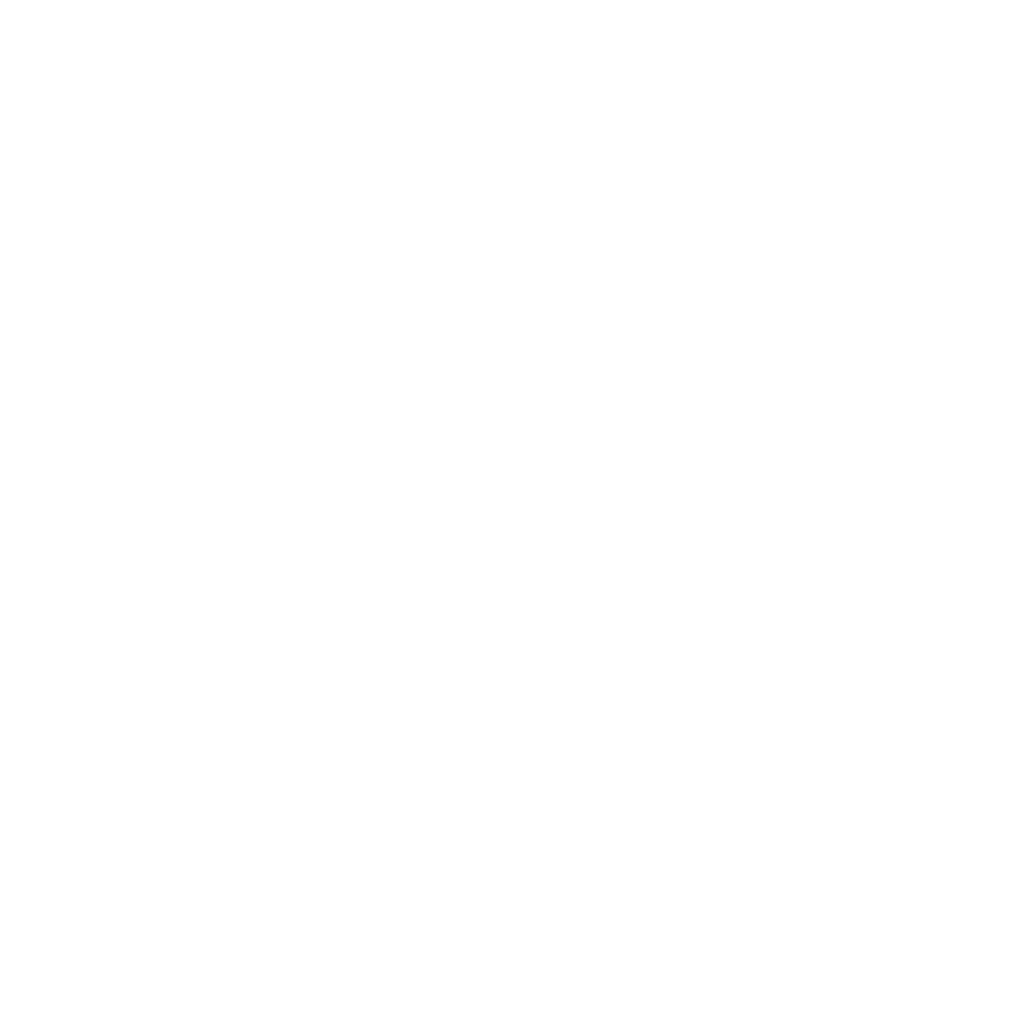

Thousands of artifacts excavated at the house reveal how black Annapolitans guarded against economic instability and mistreatment from racist whites. These finds show what the Maynard and Burgess families ate, what they bought, and where they bought it. For example, many fish bones and scales were discovered under a porch addition to the house. This indicates that the residents caught and cleaned the fish they ate rather than going, as their white counterparts did, to markets where fresh cleaned fish was widely available. Eating in the Side Room by Mark S. Warner uses the discoveries at the Maynard-Burgess House to analyze the economic and social life of free blacks in Annapolis.

John Maynard, who had been born free in Maryland in 1811, bought the property on Duke of Gloucester in 1847 from a white man who had relocated a roughly 30-year-old one-story frame structure there from a place unknown. Although the circumstances of John Maynard’s birth as a free black are not known, it was not unusual for free Africans to settle in the US by way of Europe, sometimes arriving as indentured servants. Before the 1660s skin color didn’t seem to matter much as blacks and whites alike struggled to tame the wilderness.

Hand of Fatima charms excavated at the Maynard-Burgess House may have come originally from African slaves who wore them as protection from evil spirits.

Photo courtesy of the University of Maryland.

Hand of Fatima charms excavated at the Maynard-Burgess House may have come originally from African slaves who wore them as protection from evil spirits.

Photo courtesy of the University of Maryland.

That changed in the 1660s with the growth of slavery and the decline of indentured servitude. The Maryland colonial legislature began passing discriminatory laws. One law declared that once a black person was a slave, he or she would always be a slave. This harsh position changed when slavery became less important as a labor source.

Maynard married Maria Spencer while Maria, her daughter Phebe Ann Spencer, and her mother, Phoebe Spencer, were slaves. By 1845, he had purchased their freedom. By 1850, they were all living in the house along with Maynard and Maria’s young sons, John Henry and Louis, alongside black and white neighbors. At this time, about 45 percent of the state’s black population was free; in other southern states, the percentage was no more than 10 percent.

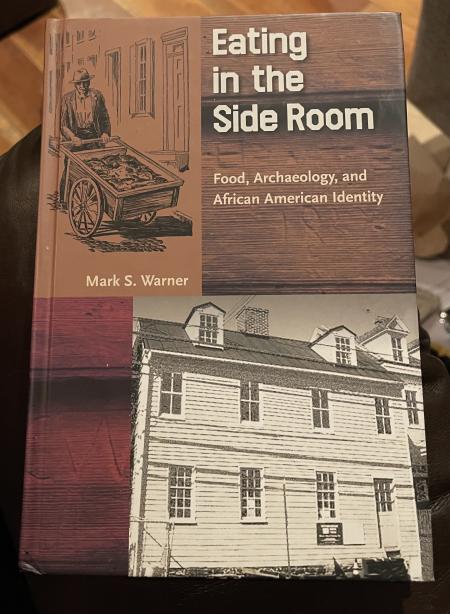

John worked as a waiter at the nearby City Hotel, and Maria took in laundry. John Henry became a barber. He also enlisted in 1866 as a landsman—the lowest rank of sailor—on the USS Marblehead.

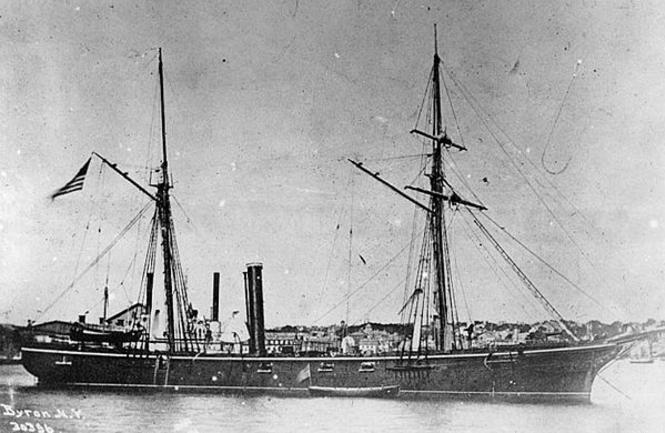

John Maynard oversaw vast changes that tripled the house’s value. He added new entrances, a second story, an attic and changed the location and size of the entrances and windows. Later on, he added a shed-roofed kitchen.

When Maynard died in Annapolis in July 1875, the inventory of his estate provided a room-by-room description of the family’s home, complete with a formal "Front Room” and more private “Side Room” for taking meals. The inventory shows that the family lived in material comfort and participated in Victorian-era consumerism by using decorative marble-top tables, processed foods and beverages, and mass-produced tableware.

The Maynard family took in boarders to replace John’s income. By 1880 the household included a widowed daughter-in-law, a granddaughter, and three boarders. Maynard descendants held onto the property until 1914, when they defaulted on the mortgage. Willis Burgess, a relative of the Maynards by marriage and a boarder in the house, bought the home. Burgess family members remained there until 1990.

Until the late 1960s Maynard and Burgess children attended segregated schools. John Maynard, who was active in Annapolis’ black community, was a trustee of the Stanton School, Annapolis’s first school for black children. As a church leader, he donated funds for a stained-glass window when the Old Mt. Moriah A.M.E. Church, now home to the Banneker-Douglas Museum, was built in 1874.

In 1993, the city acquired the home for restoration with a grant from the Maryland Historical Trust. By this summer, the Maynard-Burgess House will reopen in its newest incarnation with city offices on the first floor and the upper levels preserved to tell the story of 143 years of African-American life in Annapolis. Meanwhile, take a look at this slideshow of some of the most interesting aspects of the house.